- Home

- MacKenzie, Lily Iona;

Curva Peligrosa

Curva Peligrosa Read online

Contents

One

Bones Will Be Bones

Aftermath

Curva and the Prairies

The Greenhouse

The Bones

Billie One Eye Takes Charge

More Bones

Weed

Curva and Xavier

Sabina and Victor

The Real People

The Weedites and Curva

A Visitor

Curva & Billie

Curva and the Stranger

Curva in Motion

Two

Billie One Eye

Stampede

Vision Quest

The Coast

Billie and the Ni-tsi-ta-pi-ksi

Three

Billie & Curva

Curva & Sabina

Sabina’s Mentors

Dead Man’s Polka

Sabina and Victor To the Rescue

Billie and Henry

Curva and Ana Cristina Hernandez

Berumba

Billie and Curva

Shirley

The Berumba Delegation

Sabina

Four

Black Gold

Oil Fever

The Magician

The Gringo

The Greenhouse

Sabina and Ian

Five

Queen Bee

To the Rescue

Those Bones

Shirley

Kadeem’s Wandering Troupe

Making Music Together

Billie and Curva

Coda

Acknowledgments

Discussion Questions

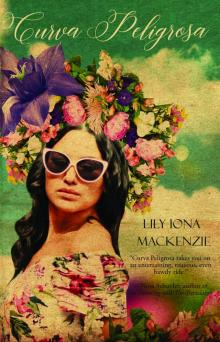

Curva Peligrosa

Lily Iona MacKenzie

Regal House Publishing

Copyright © 2018 by Lily Iona MacKenzie

Published by Regal House Publishing, LLC

Raleigh, NC 27612

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN -13 (paperback): 978-0-9912612-2-2

ISBN -13 (epub): 978-0-9988398-1-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017942121

Interior design by Lafayette & Greene

Cover design 2018 by Lafayette & Greene,

lafayetteandgreene.com

Cover photography by Valery Sidelnykov and

observe.co/Shutterstock

Regal House Publishing, LLC

https://regalhousepublishing.com

For Michael,

always my best reader

Jorge Luis Borges’ visionary fiction set out a radical vision of time and literature that implied that time is an endless repetition, fact and fiction were easily confused, and that the text one was reading was no more or less real than the life the reader was living.

—D. P. Gallagher

The imagination is the power that disimprisons the soul of fact.

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge

One

Bone Song

The dead

don’t have

cell phones.

They drift

from dream

to dream,

not waiting

for our calls

or permission

to visit. But

they eat,

appetites

voracious

and they want

news

of the living.

Bones Will Be Bones

They didn’t think much about it when the wind picked up without warning late one summer afternoon and a dark cloud hurtled towards them over the prairies. Alberta residents are used to nature’s unpredictability: snowstorms in summer; spring thaws during severe cold snaps; hail or thunderstorms appearing out of nowhere on a perfect summer day. At times, hot dry winds roar through like Satan’s breath, churning up the soil and sucking it into the air, turning the sky dark as ink. Months later, some people are still digging out from under the spewed dirt.

But this wasn’t just a windstorm. A tornado aimed directly at the town of Weed, it whipped itself into a frenzy. To the Weedites, it sounded like a freight train bearing down on them, giving off a high-pitched shriek the closer it got, like a stuck whistle. The noise drowned out everything else. Right before the tornado hit, a wall of silence descended, as if the cyclone and every living thing in the area had been struck dumb.

And then a completely intact purple outhouse dropped into the center of town, a crescent-shaped moon carved into its door. It landed right next to the Odd Fellows Hall and behind the schoolhouse. Most people thought the privy had been spared because its owner—Curva Peligrosa, a mystery since her arrival two years earlier—had been using it at the time.

Meanwhile, the tornado’s racket resumed, and Curva sat inside the outhouse, peering through a slit in the door at the village dismantling around her. The funnel sucked up whole buildings and expelled them, turning most of Weed upside down and inside out. Unhinged from houses, doors and roofs flew past, along with walls freed from their foundations. The loosening of so many buildings’ restraints released something inside Curva. Never had she been so aroused. It was more exhilarating than riding the horse she’d bartered for recently, a wild gelding. The horse excited her, especially when she imagined herself riding its huge organ. In the midst of the noise and clatter, just as the tornado reached its climax, Curva had hers.

A heavy rain followed, some of it seeping into Curva’s sanctuary and dampening the walls as well as her nightdress. So much rain pelted the town it created a flood that overran the main street. Protected from the worst of the storm, Curva drowsed and dreamt that she fell through the hole in the seat, landing on the ground with a soft thud next to a pile of bones, each about ten inches long, worn smooth from the elements. She grabbed one and—still aroused—used it, waking to the melting feeling of another orgasm and the sound of rain pelting the roof.

Aftermath

The Weedites clung to splintered roofs and walls so they wouldn’t be swept away by heavy winds and the downpour, a prelude to hail the size of baseballs that battered the already beaten-up village and its inhabitants. Some were reminded of the Biblical Flood; they thought God was punishing them. Others believed Curva was responsible. If she could ride the whirlwind safely, perhaps she could also make nature attack them.

After the tempest, this idea was clearly on their minds as they poked through what was left, their intimate lives tossed about for all to see. They cast dark glances in Curva’s direction and muttered among themselves, wondering what role she had played in their upheaval. Family photos and underwear and other personal belongings intermingled in the collective wreckage.

Despite the physical destruction of houses and homesteads, the tornado didn’t kill anyone. Some received scratches, bruises, and a few broken bones. Old Man Hawkins had a mild heart attack, but he’d been having those for as long as anyone could remember. It wouldn’t have been an occasion if he hadn’t keeled over and clutched his chest.

When the tornado had first hit, the doctor was examining Olga Matoule, a pregnant patient. Her feet in the examining table’s stirrups, she wore a dress decorated with blue forget-me-nots that hugged her belly. The doc had an eye for the ladies, and he enjoyed probing them: if he got the urge and the patient seemed willing, well, nature took its course. Neither pregnancy, nor illness, nor much of anything else restrained him. Married or single, he didn’t care. He loved them all. And the patients didn’t mind, not those, at least,

who encouraged his explorations. He offered a distraction to women whose lives were confined to tending chickens and baking bread.

Still, Mrs. Hawkins managed to find the doctor in all that rubble, not always easy under the best of circumstances since he didn’t keep regular hours. She said, My husband’s dying. We need you now!

The doctor left Olga on the examining table. Fully exposed to the world outside, her feet still in the stirrups, she witnessed the wind ripping the walls from their foundations and carrying off part of the roof. The shock brought on labor. Olga’s screams jolted awake her husband Henry, who’d been snoozing in the waiting room, its enclosure still partially intact. Olga, who knew Curva had some experience as a midwife, yelled, Get Curva, for Chrissake. This bloody baby wants out!

Frantic, Henry waded down the main street, asking if anyone had seen her. Nathan Smart, owner of Smart’s General Store, pointed at the jauntily tilting outhouse, one of the few remaining undamaged structures. Reluctantly, Henry banged on its door. With all the speculation floating around about Curva, he didn’t know what to think about her. But desperate to find someone to help his wife give birth, he couldn’t be choosy.

Half awake and half asleep, it took a few minutes for Curva to orient herself. A beatific expression on her face, a bone dangling from her right hand, and wearing only a flimsy silk nightdress, she opened the door slightly.

Henry tried to ignore Curva’s abundant body, clearly visible beneath the damp fabric. He cleared his throat: Could you help me out? The baby’s ready to come and the doctor has his hands full.

Not yet fully conscious, Curva didn’t respond immediately, so Henry repeated his request, his voice shrill and fretful.

Now fully present, Curva noted that Henry’s eyes resembled those of a frightened horse. She had delivered enough babies to know that the child’s father needed as much reassurance as the mother. She patted his arm, her touch settling him down, nodded, and followed him through the wreckage.

Up to her hips in water, unseen matter bumped against her legs. Curva ignored what she couldn’t see, intent now on helping Henry. Rain, coming in fits and starts, pelted the two of them. Curva’s long dark hair meandered about her face and bare shoulders like water snakes.

The two of them arrived at what was left of the doctor’s office just as the baby’s head, covered with a bloody sac, appeared between Olga’s spread legs. The sight of this new life entering the world filled Curva with awe, reminding her of why she had become a midwife. To witness the moment of birth, an act repeated endlessly through the ages, gave her hope. She believed childbirth conquered death and would continue to do so after she had left this world.

Curva sent Henry off to search through the ruins for dry cloths and a bucket of clean water. Between contractions, Olga panted and gasped for breath, clutching and pushing at her stomach. She let out one last scream, and in a final spasm, the baby thrust himself into the world, landing in Curva’s arms. A witness all these months to his mother’s affair with the doctor, he recognized early he would need to fend for himself and had bit through the umbilical cord, exposing a mouth filled with fully formed teeth.

By now, the rain had stopped, and Henry had returned from his errand with the needed supplies. The sun flooded everything with light and warmth. Though relieved the ordeal was over, Olga looked at the newborn and crumpled in a puddle of tears, not up to motherhood—to the sacrifice and commitment involved. Curva held the boy by his feet, head down, so the mucous could drain. After, she gave a curt whack to his round, pink bottom, and his lungs started working, too. He’s a loud one, Curva said. Olga just snorted and turned her face to what once had been a wall. The boy screamed, and Curva handed the baby to Henry, who was so nervous he almost dropped his first-born.

Through all of this commotion, Olga sniffled away. She still was glorying in the bathing suit contest she’d won when she was five months’ pregnant and didn’t want this child chewing on her pert, brown nipples. The thought of her breasts hanging around her waist in a few years from bearing and breastfeeding too many babies also upset her. Surely her good looks entitled her to more of a future than changing soiled diapers and caring for a family she didn’t want. These thoughts had grown in Olga since Curva’s arrival in Weed. Having visited her new neighbor’s place, Olga envied her unfettered liberty: Curva answered to no one but herself.

It didn’t surprise the townsfolk when, a few weeks later, the doctor decided it was time to head south, seeking a healthier climate. Driving his old Mercury, he almost ran over Olga standing near the curb, a suitcase parked on either side of her, thumb stuck out in the direction he was going. He stuffed her bags into the trunk, and the two of them headed off into the sunset together.

Curva and the Prairies

Curva, originally from Mexico, had ridden a pinto into Weed. A second horse pulled a travois, and a mangy dog limped behind a younger one that led the way. Dressed gaucho style, she had turned up at dusk, a black, flat-brimmed, flat-topped hat tilted low over her eyes, a parrot on each shoulder. Sitting high in the saddle, she looked queenly, waving graciously at the townspeople, smiling. One gold tooth glowed when she opened her mouth, and her big breasts and shapely buttocks aroused the men.

Curva had stopped near the sidewalk on the main street and brushed off her black pants, turquoise rings flashing on every finger, trousers tucked inside scuffed riding boots. Spurs clinked against the metal stirrups, and she wore a wide, ornately tooled silver buckle. A beige serape hung casually from one shoulder.

Everyone had paused—elbowing one another, mouths hanging open—and stared at this tawny-skinned woman whose striking features reminded them of Katy Jurado, the alluring Mexican actress they’d recently seen in High Noon at a Calgary cinema. Curva had the same lush lips and brooding, heavy-lidded eyes. At over six feet, she was also the tallest woman many had ever seen. Her size gave them pause: clearly all woman, yet with the strength and authority of a man, she didn’t appear to be a clingy, garden-variety female. She wasn’t even a non-clingy type. She didn’t fit into any category most were used to.

Curva surveyed the onlookers and laughed heartily at their ogling. Her response tickled their funny bones, and they joined in, eventually applauding her and her entourage as they moved past. Most thought she was heading for the Calgary Stampede to compete for title of Queen. But the rifle slung across the saddle and the two six-guns tucked into holsters riding low on her hips signaled something different.

On the move for over twenty years, Curva had ended up in Weed by chance. For much of that time, she had followed the legendary Old North Trail, a passageway that extends from the Canadian Arctic down to the deserts of Mexico and beyond. It runs along the base of the Rocky Mountains and the Continental Divide, following a kind of shoreline between the mountains and the plains for over three thousand miles. The Blackfoot call the trail “The Backbone of the World.”

Though Weed hadn’t been Curva’s original destination, her twin brother Xavier’s early death had caused her to pursue a substance that would cure all ills and prolong life indefinitely. She had thought studying nature on the trail might give her some answers. Over the years, she had tried many mixtures, thinking she was near her goal, only to be disappointed. The elixir eluded her, but not the desire to create it.

Curva wondered if the dandelion wine she made might be such a tincture. From helping her father make vino when she was a girl, she had picked up some tricks. Over the years, she had experimented with various flowers, fruits, and vegetables, learning to measure and balance ingredients like an alchemist until she had captured their essence in liquid form by soaking them in water and other fluids. The metamorphosis of earthly produce into liquor made her think she was onto something. The vino she had perfected over the years seemed miraculous, causing taciturn Canadian farmers to become talkative and animated.

If the Weedites had been aware of Curva’s interest in alchemy and tr

ansformation, they might not have been so welcoming. Such notions didn’t exist in their world. And while prairie people are usually wary of strangers, especially foreigners with a different skin color, Curva seemed oddly familiar, though for many she was the first Mexican they’d seen.

An enigma, Curva’s belly laugh rang across the prairies, producing a series of vibrations that titillated everyone, bringing a smile to their faces. The sound reminded them of something they couldn’t quite identify, teasing the edges of an ancient memory that didn’t fully form. Curva’s exuberance and natural warmth created a fire they wanted to huddle close to. But others had seen her communing with plants and animals as if she spoke their unfathomable language and they hers. The wheat growing in the fields bowed to her as she passed, and the cows nodded their heads up and down whenever she came near. These responses made her prim neighbors wonder if Curva used unnatural powers, things beyond their command or knowledge, and that made her a bit of a loose cannon as well. They feared she could alter their lives in ways they didn’t understand and use her powers against them. Though they welcomed her into their midst, in truth, the Weedites didn’t quite know what to make of the woman.

It also had seemed odd when Curva rode out of the wilderness that July day in 1953, looking for a farm to buy. Even more curious, she had the cash to pay for it, ending up with a ramshackle place a few miles outside of town. The owner had just died, and he didn’t have any next of kin. It was auctioned off to Curva, the highest bidder, though some guy named Shirley, an americano from Sweetgrass, Montana, challenged her almost to a draw.

Curva won.

The americano bowed and said, The little lady can have it.

Curva bristled at being called a little lady and glared at the hombre. But, excited about winning the bid, she didn’t pay much attention to the rude gringo. As soon as the auctioneer and other bidders had left, she surveyed her property. It included a vegetable garden, a small greenhouse, a few chickens, a rooster, cows, pigs, sheep, a broken-down horse or two, and a battered 1945 Chevy pickup. The barn wasn’t much more than an overgrown shed, the house had two small bedrooms, and the kitchen and living room were one big space. Yet to Curva, it was paraíso.

Curva Peligrosa

Curva Peligrosa