- Home

- MacKenzie, Lily Iona;

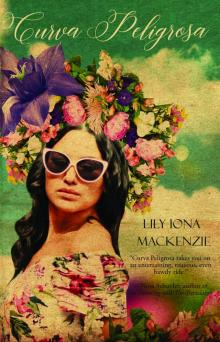

Curva Peligrosa Page 2

Curva Peligrosa Read online

Page 2

A summer shower baptized Curva’s new home and left a rainbow in its wake that arched across the blue sky. Golden wheat swallowed it at both ends, so it appeared to meet underground. Certain the rainbow contained a portent of some kind, Curva stepped outside and stared at it. The rainbow’s appearance convinced her she had chosen the right place to settle.

Curva’s horses looked ready for a home as well, and she stabled them in the barn. Then she hauled inside her travois’ contents, chased away the mice that had taken over, unpacked, and looked over her casa. Relieved to finally put down roots, she never wanted to pack up again. She’d been running for too long from her past.

Hands on hips, she prowled the rooms, pausing and nodding her head now and then in appreciation of what she saw. After sleeping on the hard ground, or living in run-down rooming houses and hotels for years, it seemed like a castillo. Thrilled, she grabbed her shotgun, ran outside, aimed at the sky, and pulled the trigger, letting out a howl to express her pleasure. A passing duck took a pellet or two and landed with a thud nearby. Even when she didn’t aim, Curva was a wicked shot. Soon, she had plucked the duck’s feathers, gutted it, removed the buckshot, and popped the bird into the oven for a celebratory dinner.

It didn’t take long for Curva to install herself, and she quickly put her mark on the place, transforming the house’s exterior to match the Mexican flag’s colors: red, green, and white—along with a yellow chimney. She painted the barn and the outhouse purple. The living room and kitchen walls ended up turquoise and yellow. She chose orange and red for the bedrooms. Curva even painted the fences surrounding her property in alternating shades of fuchsia and orange, the colors reminding her of a piñata. Alberta’s abundant sunlight combined with these vivid colors and chased away any dark thoughts that occasionally preoccupied her.

The house had electricity and a gas stove, lacking only an in-door servicio. Enjoying her new domesticity, Curva baked and sewed, planted and canned, reminded of her youth in Berumba, Honduras, when she had worked in her employer Ernesto Valenzuela Pacheco’s kitchen. Curing her own meat or growing herbs and other things she now sold was familiar to her. And her prized, homemade dandelion wine provided additional income from a readily available source: dandelions grew everywhere in Alberta. She caught those bright yellow faces in their prime and parlayed them into something potent and flavorful.

But a woman making vino? And drinking it? No self- respecting Weed female would drink spirits, at least not publically, so Curva’s loose behavior shocked some of the more conservative westerners, though not Weed’s doctor. Before he left the area, he had worn a path to Curva’s door in no time, causing tongues to wag; yet her charms seduced not only the doctor but the other townspeople as well. Curva’s fractured English, spoken with a Spanish accent, attracted them, as did the husky quality of her voice. The sound of her vocalizations reminded everyone of rocks tumbled by the river’s current, and they loved listening to her talk and sing. She would strum Xavier’s old guitar for accompaniment and sing “Besame Mucho,” closing her eyes and feeling the music deep inside her bones.

But it wasn’t just Curva’s voice and music that cast a spell on her neighbors. They also discovered her healing skills, many of them feeling better in her presence. Some even insisted that chronic backaches and limps disappeared after visiting her. Before long, the Weedites were calling on Curva to cure their ailments when the doctor was in his cups—a frequent occurrence. They thought she was better at diagnosing their problems than he was. She patted their aching bellies, clucked her tongue, and offered drinks that contained especial herbs she grew in her garden. She also gave the town folk other medicinas she had concocted, ones that mimicked the mixtures Ernesto Valenzuela Pacheco had made in his Berumba pharmacy. He had created remedies for diarrhea and stomachaches and hangovers, and she remembered their ingredients.

Nor was it unusual for townspeople to appear on her doorstep in the middle of the night, calling Curva, Curva, the baby’s almost here! Despite severe snowstorms, she jumped out of bed, threw on some clothes, and grabbed her bag of tricks, a large multi-colored patchwork satchel she’d sewn together from samples she’d picked up at church rummage sales. The bag contained clean sheets, towels, a hot water bottle, alcohol, a thermometer, scissors, needles, thread, and a jug of her dandelion wine. Then she revved up the Chevy pickup and roared out of the driveway.

An expert midwife, a skill she had learned in the Pacheco household and had practiced at times on her travels, she never turned down these requests. Assisting a mother to give birth soothed Curva. The cries of squalling babies brought her solace, reminding Curva that new life could occur even during painful periods. It also amazed her to view this passageway that gave women and men so much pleasure. Life’s origins seemed even more mysterious and wondrous when she participated in this ritual of bringing new life into the world. During these deliveries, Curva felt close to the miraculous genesis of all life.

Since many Weedites thought Curva had divine connections, they later brought their babies to her kitchen for her blessing, hoping to protect them from ill fortune. Of course, they did this secretly, after the local pastor had baptized them. Curva sprinkled a little vino on the parents’ and babies’ lips, giving them a taste for the fruits of the earth, and crooned a song to the child in Spanish that her mother had sung to Curva and to her brother Xavier:

De colores,

de colores se visten los campos

en la primavera.

De colores,

de colores son los pajaritos

que vienen de afuera.

De colores,

De colores,

vemos lucir.1

The parents thought she was chanting an ancient benediction and smiled appreciatively, believing their child was now doubly protected from harm.

It wasn’t just Curva’s healing arts or delicious vino that people sought. Her chickens produced eggs with double and triple yolks that were the talk of Weed. Her neighbors couldn’t get enough of them, believing these hens had unusual abilities, too, though they couldn’t have identified what these talents were. But the women also used the word magic to describe Curva’s gift for reading their palms and tea leaves and cards. Gathered in her kitchen, they waited in line for her to study their teacups, poking and rearranging the leaves, trying to create interesting shapes. Or they stared at the lines in their hands, wondering how these faint indentations could provide a map for Curva to interpret. Curva squinted her eyes and studied all of these things closely, whistling under her breath and exclaiming in Spanish at a line’s curve or an image that turned up in the leaves or the cards.

The women oohed and aahed about the comments she made. Often, she saw or said things that took their breath away. Catherine Hawkins, Old Man Hawkins’s child bride, nearly fainted when Curva told her there was another hombre in her future. A young one. The idea took on its own life in Catherine’s mind; she couldn’t look at a man without wondering if he was the one. The thought constantly kept her off balance.

And Edna MacGregor, the old maid schoolteacher, blushed when Curva said she had a very large Mount of Venus in her palm, a sure sign of someone with a highly sexual nature. Manuel and Pedro, Curva’s two parrots, gifts from the Pachecos, mimicked their owner: “Sex, sex, sex,” they cawed, making everyone laugh and dispelling the women’s discomfort at discussing it so openly.

But thereafter Edna often found herself staring at her own palm, even while teaching. The sight of it sparked lurid fantasies about her young students, male and female. She watched them interacting so naturally, expressing interest in one another’s bodies, their raging hormones causing Edna’s to similarly ignite. She could barely contain herself till she got home and closed the door to her bedroom. There she expelled some of her built-up arousal and gave full expression to her lust, either with her fingers or with the help of a carrot from her garden. Curva’s observations had now made

it difficult for Edna to observe her strict Presbyterian upbringing.

In no time, Curva felt like a fixture in the Weedite’s lives, her visitors paying what they could for her services, leaving fresh vegetables or canned jam if they didn’t have any spare cash. Curva bowed and smiled, flashing her gold tooth. Gracias, Gracias, she said.

Curva was also known for her excellent brownies. After munching on one of them, her visitors found themselves giddy and lighthearted, more able to face the inexhaustible demands of farm life, their appetite stimulated not just for food but also for living. Stopping by her place was like taking a mini-vacation.

But mostly they dropped in out of curiosity and for the uplift it gave them. The women especially were intrigued to have someone in their midst who ignored convention and wasn’t bound by the same rules as they were. Curva did pretty much as she pleased. No one else used bright colors to paint their houses and outbuildings. It took some getting used to, these gaudy blooms on the bland prairies, but the unusual tones grew on her neighbors, giving them a boost whenever they passed by and expanding their own palettes. Soon, other buildings showed signs of Curva’s influence. Catherine Hawkins tried an intense orange trim around her windows; Sophie Smart painted her front door turquoise; Inez Wilson brightened her chicken house with yellow.

When these women stopped by Curva’s place, they sipped a little vino or chomped on a brownie, watching their hostess bounce around the kitchen, her large breasts unconstrained by a brassiere. A blur of activity, she stirred, sifted, shook, and chopped, whipping up a medley of dishes, the odor of sizzling onions and stewing beef filling the house. While working, she chattered in a mixture of English and Spanish or sang Latin American songs. Manuel and Pedro perched on her shoulders, singing along with her.

Another attraction? Curva’s guns added to her authority. They rested on the kitchen counter within easy reach should someone break in unexpectedly. The domestic surroundings made them seem almost innocent and incapable of inflicting harm. Female visitors glanced longingly at them. A few reached out and touched their smooth surface, soft as baby’s skin. As for the men, when they stopped by Curva’s place, they avoided the firearms altogether, ignoring their presence, unwilling to acknowledge that a woman might have the upper hand with such things.

When her visitors left, they carried Curva with them, her unintelligible words still echoing in their ears. The Latin rhythms possessed their bodies and feet (the vino and brownies also contributed), so they had trouble walking a straight line. Arms swinging to the music, they circled and swayed, finding it difficult to move forward. For the women, visions of swarthy, dark-haired, hot-blooded men made them dissatisfied with their lighter-skinned husbands. The men shared similar fantasies, only theirs were of females like Curva.

The men also wondered what she was up to with the farm. The property included an extra half-section of land, much of it in summer fallow. Curva didn’t waste any time leasing out most of it to a local farmer because she liked his last name—Paris. He gave her a percentage of the crop. The men also wanted to know just how friendly she was. Everyone hoped that by getting a glimpse inside her house, they might figure out her game, so they dropped in to buy eggs or whatever else she had for sale.

They sniffed and gawked, checking the walls and built-in shelves and mantle for pictures or letters that would tell a story, but except for the vibrant colors, the place was pretty standard—and pretty bare, other than the hens wandering in and out, pecking on bits of ground cornmeal Curva had dropped on the kitchen floor. The main room contained scarred wooden chairs and a table the previous owner had made; a flowered yellow oilcloth that curled around the edges covered the top. Propped against a wall stood a sagging chesterfield in a faded blue slipcover; a rocking chair faced it. And in the center was a wood-burning stove.

A few pictures of unfamiliar settings and what looked like an Indian medicine bag hung on the walls. Yet what really caught their attention were several blue ribbons. Some of the visitors assumed she had earned them for baking, but they were wrong. Curva had followed the rodeo circuit for years, proving herself in the ring as a champion broncobuster and bull rider. The purses she won had bankrolled the farm. Curva also was an expert sharpshooter and could nail a fly from thirty feet—a skill that also had put a few dollars in her pocket.

The many green plants contributed to the distinctiveness of her home, varieties the townspeople had never seen before. No one else kept plants inside the house. But Curva wasn’t much of a housekeeper and didn’t waste time chasing dust balls or dirt. Yet she always had a saucepan full of something stewing on the stove, the exotic smells unlike the usual pot roast or stuffed cabbage leaves that most women cooked. Curva’s food flooded the house with odors of her homegrown hierbas and especias. They transformed even the most banal ingredients, turning them into a gourmand’s delight: chicken mole, chayote corn soup, cumin-crusted pork, dishes she’d learned to make while working for the Pachecos. Curva shared her skills with the women hanging out in her kitchen, her deft hands shaping tortillas and creating succulent sauces.

When Curva merged meats and vegetables and various especias, they produced something unique and flavorful. Similarly, when she sowed seeds or seedlings, they took root and went through many transitions, growing from tiny seeds into fully grown plants, different at every stage, no two the same. So did various insects, but especially butterflies. As a child in Mexico, she’d watched the Monarchs return each year from Canada and had wondered about the source of their fertility and stamina. Now she could finally investigate them within her greenhouse, a laboratory where she explored their transformations.

* * *

1 Painted in colors, the fields are dressed in colors in spring. Painted in colors, painted in colors are the little birds which come from the outside. Painted with colors, painted with colors is the rainbow that we see shining brilliantly above.

The Greenhouse

Curva enlarged the glass-enclosed shed that came with her property, doing most of the construction herself. Bigger than her living quarters, the greenhouse was crammed with Curva’s collection of flora that threatened to overflow the space. Colorful blossoms and green leaves pressed against the glass, their tendrils seeking cracks and crevices from which to extend themselves.

Morning and night, she sang her favorite songs while puttering with the plants, her vocalizations attracting numerous songbirds (prairie larks, wood thrushes, finches, yellow warblers), all drawn to her sanctuary and taking up residence there. Like bees around a hive, they hovered above her as she flitted around, often in the nude— watering, fertilizing, feeding. She liked the freedom of being naked, especially with her plants and animals. They didn’t wear anything. Why should she? Her waist-length hair fell over her breasts and sensuously stroked them each time she moved.

Her skin felt as if it had feelers, the tiny hairs picking up on the slightest breeze and making her shiver with delight. It reminded her of traveling on the trail. In warm weather, she sometimes went for days without wearing any clothes. She also loved it when the sun penetrated her body like a lover. Clothing created artificial boundaries, and to be free of them for a time was liberating.

One day, Catherine Hawkins stopped by the greenhouse and found Curva flitting about in her birthday suit. Of course, after her visit, Catherine stopped at Smart’s store and whispered in Sophie Smart’s ear that Curva had been working naked in her hothouse. Both women sniggered. Before long, everyone in Weed was talking about Curva the nudist. The story took on its own life, flourishing like the lush plants in her greenhouse, with each person adding embellishments until no one knew quite what to believe. Some of the Weedites wondered if she should be charged with indecent exposure. But no one had the courage to alert the authorities, and, after all, Curva was on her own property. Besides, no one wanted to be responsible for having her arrested: she had become too valuable to the Weedites and they had developed a tas

te for her dandelion wine and other ministrations.

Though Catherine Hawkins was shocked at her new neighbor’s boldness, it didn’t stop her from secretly housecleaning in the buff. Having her breasts and genitals so exposed while she swept the floor and washed the dishes increased Catherine’s sexual fantasies, and her ardor surprised her husband at the end of the day. And Sophie Smart? She tried weeding nude in her garden, hoping to get the hang of what Curva was doing. But the mosquitoes ganged up on her, and so did the black flies, leaving her feeling like a pincushion.

As a result, a flood of Weedites, men and women, dropped by Curva’s whenever they could to observe her, pressing their faces against the greenhouse glass and steaming it up with their heated breath. Since she wasn’t concerned if someone saw her naked, word soon spread about her splendid curves and unconventional attitude. Everyone also talked about her green thumb and her birds. In their minds, Curva’s ability to make things grow in a hostile climate somehow got mixed up with having second sight and other powers.

No one realized that Curva’s madre had been known as the curer of multiple maladies. She had taught her daughter about growing plants, passing on tricks for making medicines from them. Curva’s madre could bring the scraggliest, dried-out stick back to life. Look at what she had done for Curva, who’d been a scrawny, waif-like kid. All bones. Scared of her shadow. But her madre soon took care of that. She fattened up the girl and drove away her fears with potions and chanting. Curva’s madre had also awakened her daughter’s interest in the healing arts. Curva’s curiosity about immortality came later. With the right clues, Curva hoped her greenhouse and its inhabitants would reveal their secrets, deepening her understanding of life’s mysteries.

Curva Peligrosa

Curva Peligrosa